- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Muted Implications (Clay Warrior Stories Book 12)

Muted Implications (Clay Warrior Stories Book 12) Fatal Obligation

Fatal Obligation Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 2

Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 2 Uncertain Honor

Uncertain Honor Neptune's Fury

Neptune's Fury Fortune Reigns

Fortune Reigns Op File Treason

Op File Treason Rome's Tribune (Clay Warrior Stories Book 14)

Rome's Tribune (Clay Warrior Stories Book 14) Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 1

Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 1 Serpent Circles

Serpent Circles Reluctant Siege

Reluctant Siege Infinite Courage

Infinite Courage Death Caller (Clay Warrior Stories Book 13)

Death Caller (Clay Warrior Stories Book 13) Op File Sanction

Op File Sanction Tribune's Oath (Clay Warrior Stories Book 17)

Tribune's Oath (Clay Warrior Stories Book 17) Galactic Council Realm 1: On Station

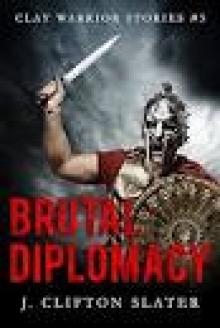

Galactic Council Realm 1: On Station Brutal Diplomacy

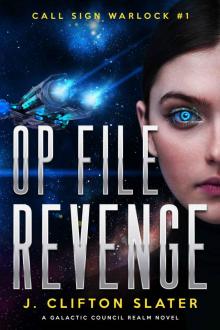

Brutal Diplomacy Op File Revenge

Op File Revenge On Point

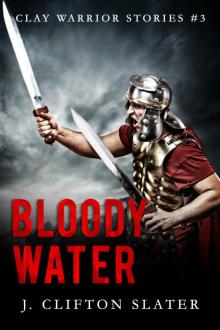

On Point Bloody Water (Clay Warrior Stories Book 3)

Bloody Water (Clay Warrior Stories Book 3) Galactic Council Realm 2: On Duty

Galactic Council Realm 2: On Duty Galactic Council Realm 3: On Guard

Galactic Council Realm 3: On Guard Clay Legionary (Clay Warrior Stories Book 1)

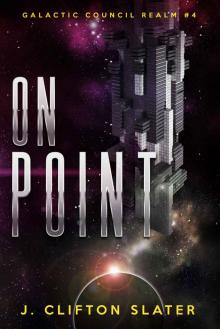

Clay Legionary (Clay Warrior Stories Book 1) On Point (Galactic Council Realm Book 4)

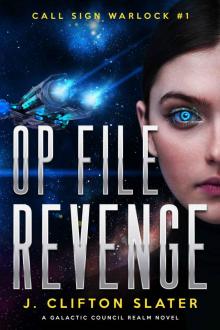

On Point (Galactic Council Realm Book 4) Op File Revenge (Call Sign Warlock Book 1)

Op File Revenge (Call Sign Warlock Book 1)