- Home

- J. Clifton Slater

Reluctant Siege

Reluctant Siege Read online

Reluctant Siege

Clay Warrior Stories

J. Clifton Slater

Books by J. Clifton Slater

Military Adventure both Future & Ancient

Clay Warrior Stories

Clay Legionary

Spilled Blood

Bloody Water

Reluctant Siege

Galactic Council Realm

On Station

On Duty

On Guard

On Point

This is a work of fiction. While some characters are historical figures, the majority are fictional. Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

Reluctant Siege takes place in late 265 B.C. to early 264 B.C. when Rome was a Republic and before the Imperial Roman Empire conquered the world. While I have attempted to stay true to the era, I am not an historian. If you are a true aficionado of the times, I apologize in advance.

I’d like to thank my editor Hollis Jones for her work in correcting my rambling sentences and overly flowery prose.

Now… Forget your car, your television, your computer and smart phone - it’s time to journey back to when making clay bricks and steel were the height of technology.

J. Clifton Slater

E-Mail: [email protected]

Twitter: @GalacticCRealm

FB: facebook.com/Galactic Council Realm & Clay Warrior Stories

Reluctant Siege

The Republic organized its army in regional garrisons. When faced with a rebellion, or threats from tribes or barbarians, the Senate approved a Legion for that specific enemy. One of the two Consuls assembled the Legion and assumed the title of General. Most of these Legions were victorious, some were not. Most of these politicians turned General were military leaders, others were not.

In 265 BC, Consul Quintus Fabius Gurges marched his Legion north to put down an Etruscan rebellion. The Etruscan city of Volsinii sat atop a fortified plateau in what today is the Tuscany region. Volsinii’s defenders were prepared for the Legion. As a result, General Gurges’ campaign wasn’t a success.

Reluctant Siege

Act 1

Chapter 1 – The Slopes of Volsinii

The Legion’s reinforced camp sat a mile to the east. Not far from where the Tiber river slashed through the wide valley. Three days ago, General Gurges marched his army up from the Capital and constructed the camp. Bypassing the hills and peaks lying to the town’s south and west, Gurges, for once, followed the recommendations of his officers. They had suggested an attack from the north. However, they had also recommended placing the Legion camp on the plain and not adjacent to the Tiber river.

The tilted plain on the north started at the base of the steep slope leading up to Volsinii. It spread out to cover half the width of the plateaued city and, unlike the other sides where the slopes resembled near vertical walls, the plain faced a climbable grade. Although not perfect, the plain allowed for staging and maneuvering of the maniples’ ranks that made up the Legion’s assaulting force.

His staff did caution, the drawbacks to the plain were the foothills ending at the southwest flowing Tiber. Besides the ability for an enemy force to hide in the hills, the riverbank could act as a road for any tribesmen coming from the north.

The other issue was the distance to the sturdy walls of the camp where the pack animals and Legion’s heavy weapons were stored. But, this was an assault not a siege. The ballistae, or bolt throwers, shouldn’t be needed.

Consul Gurges who had raised the Legion, named it after himself, and took the mantle of General, discounted the warnings. As he explained after sacrificing a bull to Victoria, “The Goddess of Victory will grant us a swift end to this affair.”

Many Legionaries commented about the General’s failure to also sacrifice to Victoria’s siblings – Kratos, Bia, and Zelus asking for Strength, Force and Zeal. The views were whispered among the ranks of Legionnaires. One didn’t openly voice an opinion about a nobleman’s actions. Seeing as Gurges was a Consul serving the last weeks of his one-year term as a Co-Consul of the Republic, and their General, all ranks were below Quintus Fabius Gurges.

***

The skirmishers raced through the ranks of the maniples and launched javelins. Many of the Etruscī and Insubri rebels held tribal shields. By shifting them, they avoided the iron heads of the Legionaries’ weapons as the deadly tips rose to the height of the rebel lines. Four of the rebel warriors standing on the plateau fell back and out of sight.

When their supply of javelins was exhausted, the Velites drew gladii and scrambled up the steep slope. In a hail of stones, arrows, and spears, the skirmishers forfeited their lives to test the resolve of the rebels. Before the skirmishers were completely decimated, trumpets sounded the recall. Now released from their assault on the heights, the Velites raced down the hill and filtered back through the lines of the maniples.

“It appears the rebels will not easily surrender the high ground,” General Gurges stated to the mounted Tribunes crowded around his horse. None of the young noblemen expected the rebels to give up. The Centurion and his escort, sent yesterday to demand the surrender of Volsinii, had returned filled with Etruscan arrows and knife slashes. Neither survived their injuries.

“I guess, we do this the hard way,” Gurges announced then waved a dismissive hand at his Tribunes. “Go prepare your sections and report back here when you’ve completed your tasks. Trumpeter, prepare to sound the advance for the first rank.”

Off to the side of the General, Colonel Pholus sat on his horse surrounded by four of the Legion’s senior Centurions. Although he could hear the General, his eyes weren’t on Gurges. They were fixed on the bodies of the Velites left behind when the skirmishers retreated. Most lay still, but every so often, a few of the bodies came to life and attempted to crawl or roll down the hill. This movement attracted arrows, rocks and spears from the rebels. Soon, all the bodies of the Legion’s skirmishers were dead.

“Butcher,” whispered a Centurion.

Pholus ripped his eyes from the bloody slope and snapped his head around.

“Yes. We will have an officers’ meeting this evening to discuss lessons learned from the assault, Centurion,” the Legion’s Colonel announced as if the Centurion had asked a question. “Until then, get to your Centuries and buck up your NCOs.”

The four senior Centurions kicked their horses into motion heading for their sectors.

“They are obstinate, don’t you think, Colonel Pholus?” Gurges called across the gap between the two leaders of the Legion. Pholus swallowed hard and his stomach turned before he noticed the General was pointing at the heights of Volsinii.

“Yes, Sir. It’ll be costly to remove the rebels,” Pholus replied. As a professional military leader, his answer referred to the lives and limbs lost by Legionaries to pacify the town.

“Not to worry Pholus. I should more than break even once I sell the spoils of war and fill my slave pens,” Gurges explained using a different definition of cost. “And best of all, I’ll be a hero of the citizens. That will serve me well when my term as Consul ends and I resume my seat in the Senate. Nothing holds sway in politics like being a hero of the people. Wouldn’t you agree?”

“Yes, General. Maybe you can hold a parade?” suggested Pholus with a hint of sarcasm.

“A grand idea, Colonel,” Gurges exclaimed. “It’ll cut into my profits but, the people do love to cheer a hero of the Republic.”

***

All Consuls when they organized a Legion to engage a large threat were arrogant. Most however, listened to their experienced core of military leaders who ran the army. Gurges had little to say until he looked at a map of Volsinii during the march north. Then, he announced his battle plan and how

he would disperse the Legion.

“Two days tops to put the rebels to death,” the Consul, with no military experience, announced. “We’ll use the skirmishers to clear the heights and the infantry can dance into the town. I imagine a cavalry charge will be thrilling to watch. Great sport, don’t you think?”

At the time, Colonel Pholus and the officers from Planning and Strategies had stood with eyes downcast as the General moved blocks of colored wood around the map. As if the troops, represented by the blocks, were skating on a flat icy pond rather than attacking up the face of a defended slope. Even later, when Pholus explained the small numbers on the map denoted elevations, the General refused to change his plan. Then, Gurges reminded Pholus that the General was a Consul of the Republic and the Colonel was from a farming family. Thusly, the Colonel should be cautious when contradicting his betters. The attack would go just as the General planned.

***

Pholus was ignored as the gang of Tribunes returned from alerting their sections along the lines of Legionaries. Each had raced to a Century’s Centurion, shouted at the officer before kneeing their mount on to the next Century. Once they finished, the young noblemen raced back to the General as if this was a game. Pholus glanced at the bodies on the hillside and back at the converging Tribunes. They hadn’t stopped to consider the cost in lives so far, or the lives of those preparing for the actual assault. Just one Tribune seemed to even acknowledge the deaths.

Tribune Peregrinus’ horse was trotting rather than galloping back to the command staff. He was the youngest of the noblemen on the General’s personal staff. After alerting his sections, Peregrinus took time to stare at the bodies on the hillside as his horse closed with the crowd surrounding the General.

“I have a change,” announced Gurges to his Tribunes while he glared at Colonel Pholus. “Remember this lads, flexibility in negotiations is important to winning. Not giving in to every weak idea from your secretaries, but being cognizant of areas where you can improve your position while seeming to give in. That will prove valuable to you, later in life.”

Tribune Peregrinus rode up as the General finished his political sermon.

“Mister Peregrinus. Did you have a nice stroll among the common soldiers?” demanded the General. Then he continued without waiting for an answer, “I’ll sound the advance for second rank when the first maniple is half way up. However, I want the cavalry repositioned. I was going to wait until they had a path to charge but, as I can see now, they’ll be more valuable on the line. Split them in half and place the cavalry on either end of the third maniple. We’ll get the rebels in a pincer movement. Go, alert your sections.”

Once again, the Tribunes raced away while Colonel Pholus almost puked. They had little enough cavalry, and now the mounted units were being split and committed to the fight. Worst of all, the battle was just beginning and the General had left no units guarding the Legion’s rear.

***

The three ranks of Legionaries launched javelins. A few Etruscī and Insubri warriors died but most of the javelins fell short. With the first maniple moving, the rebels had to come off their hill and engage. If they didn’t, the line of Legionaries would reach the top and it would become a shield wall fight for the town. Ambush and open field fighting were the tribesmen’s preferred strategies. Shield to shield, close in carnage, belonged to the Legionaries. The first maniple was six paces into the assault when the rebels committed.

A Legion’s heavy infantry was divided into three lines of the maniples. The third line composed of hardened veterans. In front of them, the line consisted of experienced Legionaries. Out front, on the first line, were rookies and inexperienced Legionaries. The idea was to get the newest Legionaries combat experience and to toughen them up by allowing them first blood.

From the top of the hill town, tribesmen poured over the crest and ran, in mass, down the steep hill. Colonel Pholus watched as the first line locked shields and braced for the onslaught. The General hadn’t ordered the second line forward. Mostly because the Legionaries hadn’t gone far enough up the slope to suit his plan. By the time the wave of rebels reached the first maniple, they were sprinting to stay on their feet. They hit the Legionaries like a herd of stampeding Aurochs. In spots, the line held. At other places, the tribesmen pounded through the shields.

Their momentum broken from hitting the shields, the rebels easily reversed course and attacked the Legionaries from behind.

***

“We’re sending up the second line. Go lads,” the General announced in a voice that spoke of controlled confidence. Probably the voice he uses while debating in the Senate, assumed Pholus. As the Tribunes kneed their horses into motion, Gurges spoke to the trumpeter, “Stand by to advance the second line.”

Colonel Pholus wanted to gallop his horse at the General and run the old wind bag over. While Gurges waited for everyone to be in place, the first maniple fought for their lives in a melee with the tribesmen.

Along the busted line, rebels and Legionaries hacked, blocked and stabbed each other. Murder and death being just a breath or a misstep away. In front of and behind them, and sometimes beside them, the rookie Legionaries blocked and stabbed trying to make sense of their broken line. Their training had prepared them to hold a line, use a shield and a gladius in unison with fellow Legionaries. And to maintain alignment while maneuvering. In other words, they were trained very well, but for combat in ranks, not as pit fighters.

Grunts, cries of madness and pain accompanied drops and splatters of blood soaring around the combatants. Soon, no one could tell if the red stains were theirs, a comrade’s, or the blood of an enemy. About a third of the inexperienced Legionaries of the front line were down when the trumpets sounded.

The experienced Legionaries from the second maniple stepped forward and joined in the gladii fighting. When possible, a Legionary would reach out and pull a rookie out of the fight and thrust him behind the line. As more and more of the surviving first line were pulled out of combat, Corporals began shoving javelins into their hands and forming them up as a second rank. Their training fit this type of fighting and they began stabbing over the shoulders of the second maniple.

***

Being proficient with the javelin and protecting the man in front of you was important for three reasons. If you kept the enemy from taking down the man in front, you wouldn’t have to be in a belly-to-belly sword fight. Also, staying with your maniple increased your chances of survival. When the skills of Legionaries on either side were equal to yours, and you knew the men, you had confidence that no stray spear or sword point would slip in from the side. And finally, there was pride in being part of a maniple. After the battle, you would share tales of heroics and stupidity by the rank in front of you. If you entered the front line, you’d be teased about your weak javelin work or your maniple would mourn your death. So, keeping the enemy off the man in front of you was indeed important.

The second maniple with help from the survivors of the first maniple, began to gain ground. As the experienced Legionaries hacked down the rebels in front of them, they used the space to take half steps forward. Soon, they were a full third of the way up the steep hill.

Behind them, the hardened veterans waited. Their chance would come at the top of the slope where the fighting would be the most vicious.

***

The Tribunes sat their mounts in a loose formation around the General. Everyone relaxed a little as the Legionaries took back control of the battle.

“Just as I planned,” bragged General Gurges. “We’ve pulled the majority of the rebels out of their merda-hole and brought them to the tip of our gladii.”

A fire on the summit flared to life. When an amphora of olive oil was tossed on the flames, a column of black smoke rose high into the cloudless sky. Then, an Etruscī horn blared. The deep resonance floated over the struggling warriors and Legionaries.

The beating of swords and gladii against armor and flesh continued. What changed was

the addition of professional soldiers to the rebel forces. Ranks of ordered Etruscans crested the hill and marched down the steep slope to join the battle.

***

After years of fighting and vicious engagements, the Etruscan civilization had been forced to sign treaties with the Republic. For two decades, they had supplied warriors to the Republic’s army. Now, some of those trained by Legionaries were turning the skills and weaponry against their teachers.

The arrival of disciplined troops went unseen by the rookies and the experienced Legionaries. They were living and dying in a narrow world of pain and sweat. Their survival counted in heartbeats left no spare moment to take their eyes off the next screaming barbarian.

Several hundred of the twelve hundred twenty hardened veterans of the third maniple noticed the soldiers. But, without a signal from the General, the best fighters of the Legion couldn’t move up. Although the addition of armored Etruscan soldiers was seen, the information was useless.

To the rear of the battle line, one person did notice the nine hundred Etruscan soldiers. General Gurges waved his Tribune corps into a horse mounted huddle.

Chapter 2 - Unexpected Rebel Formation

“I’m moving up the third maniple,” General Gurges explained. “Wait for the trumpets. Then we’ll see how those traitorous barbarians fare against our best.”

“General. The horn, I understand,” commented Tribune Peregrinus. “But why did the rebels light a signal fire.”

Pollenius Armenius Peregrinus was sixteen and the eldest son of a wealthy family with political connections. His assignment to Consul Gurges’ staff was only a way to give the lad military experience. Years from now, Pollenius could use his Legion time to further his political ambitions. When General Gurges brought the Legion together to crush the Etruscan uprising, it presented an opportunity. An easy win and useful experience, his father boasted as he packed his son off to war.

Muted Implications (Clay Warrior Stories Book 12)

Muted Implications (Clay Warrior Stories Book 12) Fatal Obligation

Fatal Obligation Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 2

Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 2 Uncertain Honor

Uncertain Honor Neptune's Fury

Neptune's Fury Fortune Reigns

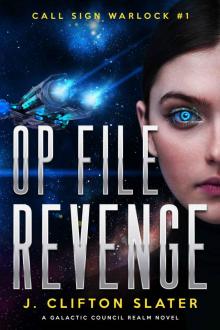

Fortune Reigns Op File Treason

Op File Treason Rome's Tribune (Clay Warrior Stories Book 14)

Rome's Tribune (Clay Warrior Stories Book 14) Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 1

Clay Warrior Stories Boxset 1 Serpent Circles

Serpent Circles Reluctant Siege

Reluctant Siege Infinite Courage

Infinite Courage Death Caller (Clay Warrior Stories Book 13)

Death Caller (Clay Warrior Stories Book 13) Op File Sanction

Op File Sanction Tribune's Oath (Clay Warrior Stories Book 17)

Tribune's Oath (Clay Warrior Stories Book 17) Galactic Council Realm 1: On Station

Galactic Council Realm 1: On Station Brutal Diplomacy

Brutal Diplomacy Op File Revenge

Op File Revenge On Point

On Point Bloody Water (Clay Warrior Stories Book 3)

Bloody Water (Clay Warrior Stories Book 3) Galactic Council Realm 2: On Duty

Galactic Council Realm 2: On Duty Galactic Council Realm 3: On Guard

Galactic Council Realm 3: On Guard Clay Legionary (Clay Warrior Stories Book 1)

Clay Legionary (Clay Warrior Stories Book 1) On Point (Galactic Council Realm Book 4)

On Point (Galactic Council Realm Book 4) Op File Revenge (Call Sign Warlock Book 1)

Op File Revenge (Call Sign Warlock Book 1)